Best Practices for Text Message Surveys

By Kevin Collins

Last month, our Chief Research Officer Kevin Collins delivered a webinar presentation for the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) on best practices for text message surveys. As the leading practitioners and original researchers of this form of data collection, we were selected to give an hour-long presentation featuring results from five years of AAPOR conference presentations, plus some hot-off-the-presses findings.

Below we are sharing eight key takeaways from the presentation. The full webinar will be available to AAPOR members here – but if you’re interesting in chatting about the results (or if you don’t have access to the link), please reach out.

Takeaway 1: Best practices for a mode of communication are inextricably linked to the affordances specific to that technology.

You cannot build best practices by simply taking what works for phone or email surveys and assume they will work for texting as well, because each mode has different affordances. In particular, texting has three we encourage all users to consider carefully. First, texting is interactive, which means while you can treat it as a single blast message like you might treat a post card, that misses some of the potential. Second, like email but unlike phones, texting is persistent, meaning that a message waits for you in your inbox when you have time to check a message. And third (putting the first two together) texting is asynchronous, which has substantial implications for cost, timing, and other aspects of fielding a survey.

Takeaway 2: Costs and benefits matter for participation, but not how you might think.

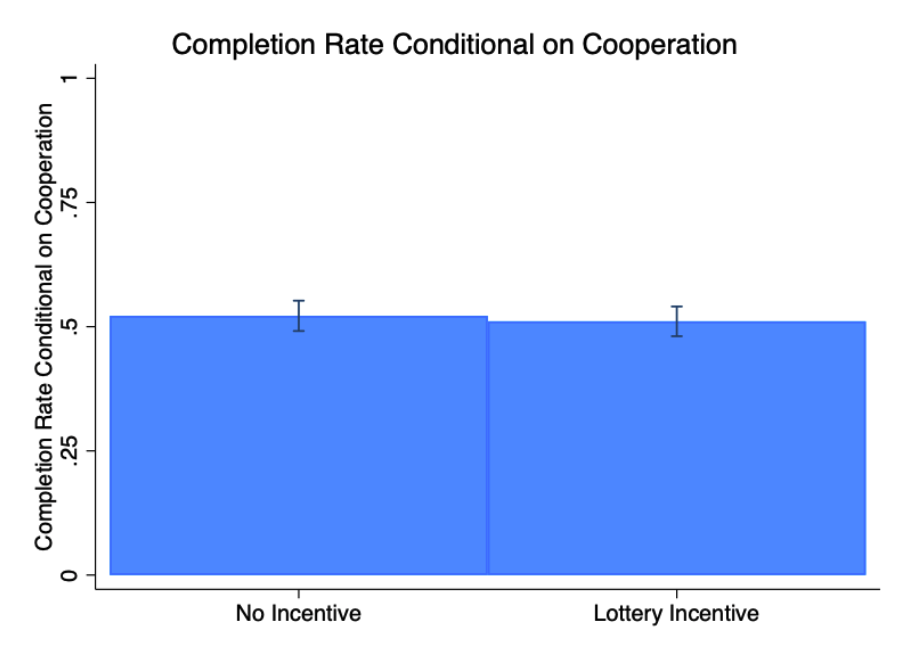

In general we have not seen large effects from small, fixed, post-paid incentives on participation. To test the effect of lottery-based incentives, where respondents who participated got a chance to be entered for a drawing for a $100 gift card, we fielded a test in a survey in August. Like previous work, we found null (and slightly negative) results on completion rate conditional on cooperation (the incentive message came after respondents agreed to participate in the survey).

In the past we have seen larger incentives ($10 or more, for instance) increase participation, but because the cost per contact is so low, the effect on response rate is not enough to offset the incentive itself. While there may be particular cases where incentives are warranted, such as panel surveys or very small populations, we generally advise against them.

We think researchers need to pay more attention to the cost side of the cost-benefit calculation. In past work we found that respondents are sensitive to the cues the text message provides about survey length when deciding whether or not to participate.

Takeaway 3: “Texting” encompasses multiple modes of communication, some of which work better than others.

A “text message survey” means more than one thing. First, it can mean either text-to-web surveys, the more common version, where respondents are sent a link to an online survey platform they then self-administer, or it can mean an interactive survey where participants respond to questions in their text message app. we have found that the interactive “live interviewer SMS” approach generally works better for short surveys, but text-to-web is a better choice for longer surveys.

Additionally, “texting” covers both text-only SMS messages and multi-media MMS messages. Which works better and when? We find that MMS – sometimes using brand images, sometimes with more "infographic" approaches designed to convey trust-inducing messages – generally works worse than SMS. We have written about this before on the blog here, but have since updated our meta-analysis with additional studies, (the forest plot of effects on cooperation rate is below), increasing our certainty in this result.

Takeaway 4: Timing matters.

Many of the decisions about how to field a text message survey are about timing: when to field, how long, with how many re-attempts. The persistent nature of SMS communication means that how you might answer these questions with phones or email may not apply for text message surveys. We have found that texting later in the evening is inadvisable, that leaving surveys open for long a period of time does not substantially improve performance, but that multiple rounds of attempts to non-responders does improve demographic balance.

Takeaway 5: Account for non-response patterns with tech-enabled stratification.

Like any mode, some people are more likely to respond to a text message survey, and some people are less likely to do so. Furthermore, these patterns can differ between interactive text surveys and text-to-web surveys. We recommend using surveys to inform expected response rates across sampling strata, and over-sample low responding groups. Furthermore we advise using Dynamic Response-rate Adjusted Stratified Sampling (or DRASS for short) to update these relative response rates in real time in order to reduce design effects and increase accuracy.

Takeaway 6: When combining texting with live phones, start with texting and backfill with live phones.

The asynchronous nature of texting makes it much cheaper than live interviewer phones. But phones can sometimes reach people that texting cannot, so in research fielded in 2023, we found that when combining modes, researchers can improve accuracy by adding live calls to the lower cost text option.

Takeaway 7: When combining texting with opt-in online panels, use the probability text-surveys to better calibrate the non-probability panels.

In research fielded in October 2024, we found that online panels have more professional respondents than text-to-web surveys yielded. That is to say, the panelists took surveys faster, missed fewer attention checks, but also reported taking many, many more other surveys. However, they were also less accurate on their own. But we found that by using information about how many surveys respondents reported taking, and treating the estimate from the probability text message survey as a benchmark, and downweighting professional respondents in the panel, we could improve accuracy.

Takeaway 8: Best practices require repeated experimentation

We rely on rigorous randomized controlled trials to inform best practices wherever possible. And not just one, either. Rather we aim to produce recommendations through meta-analysis of repeated experimentation, so we can ensure that the results are not either a fluke or the result of a specific survey context. We encourage others to do so as well.

If you are conducting experiments on how to field text message surveys (or want to), please reach out to us at info@survey160.com so we can get better together.